Orbital is a novel by Samantha Harvey, published in November 2023. It describes one day in the life of a fictional crew aboard the International Space Station, orbiting Earth at 17,000 miles an hour, moving through sixteen dawns and nightfalls.

The International Space Station is a highly technical piece of equipment. Let me suggest a parallel – Orbital is a highly technical piece of writing. I think it fitting we take off an inspection panel marked ‘Danger – Fiction Technique’ and have a look at some of the workings.

After reading articles by the excellent Emma Darwin, I have recently been thinking about an aspect of writing known as psychic distance. This sounds like some kind of new age spiritual practice, but it’s actually a description of how close a reader feels to the characters they are reading about. Are we looking at them from the outside, or are we actually in their heads? Writing tutor John Gardner breaks down the spectrum of distance as follows:

1. It was winter of the year 1853. A large man stepped out of a doorway.

2. Henry J. Warburton had never much cared for snowstorms.

3. Henry hated snowstorms.

4. God how he hated these damn snowstorms.

5. Snow. Under your collar, down inside your shoes, freezing and plugging up your miserable soul.

The idea is, with each step, a reader goes further and further into the head of Henry J. Warburton. We go from an omnipotent author telling us about him, to shivering along with Warburton in the snow.

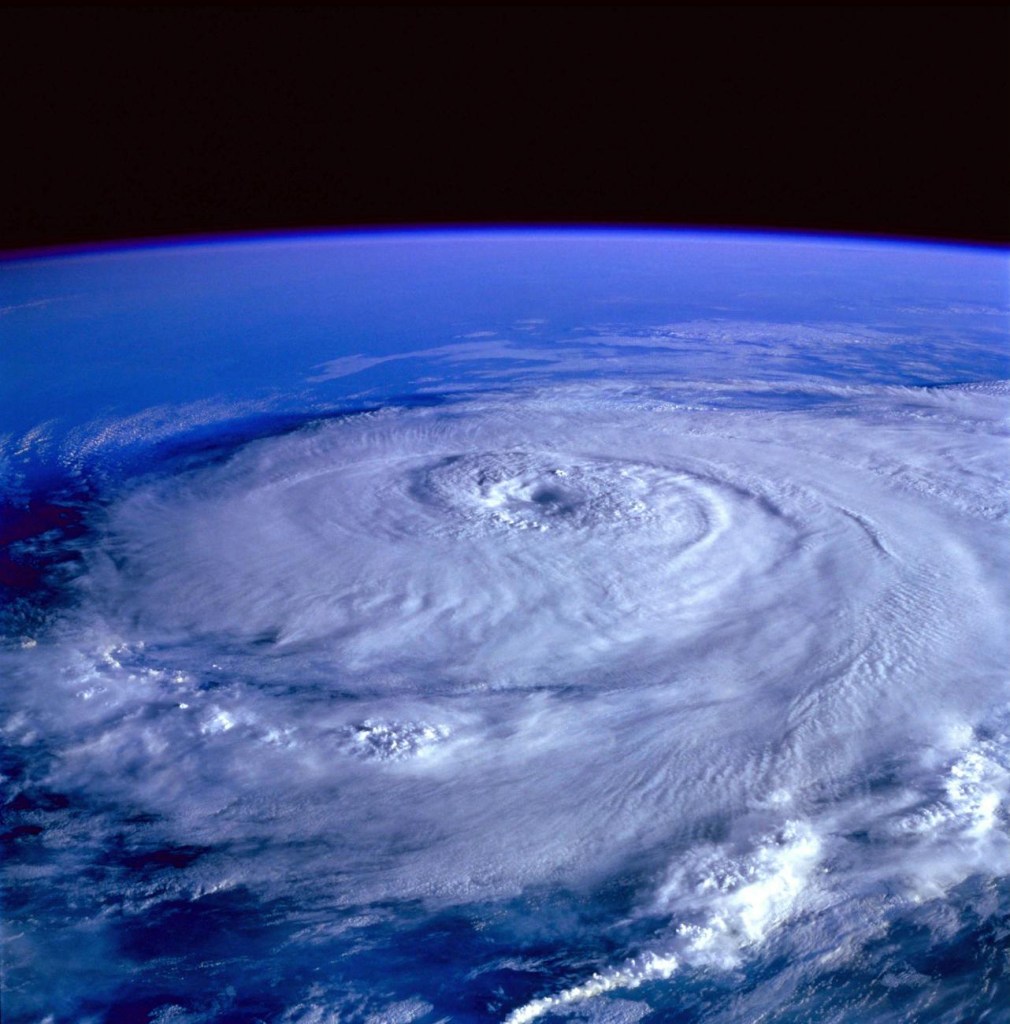

Interestingly, Orbital is mostly at number 1 in this scheme. The ISS floats over Earth just as the writing style floats over its subject. Occasionally we plunge down to number 5, like a capsule engaged in a flaming re-entry. But generally we float with great peace and wonder, hundreds of miles high, at number 1. There is no plot to speak of. Our desire to read on does not come from identifying with a particular character and wondering what will happen to them. We are above such things. This is very unusual for a novel, and allows for some remarkable descriptions of Earth, space and humanity. Not confined to the point of view of a single character, it’s possible to drift about the universe.

The price for this lies in reduced involvement. We can go anywhere but maybe care less when we get there. Is it a price worth paying?

Consider this. When I was little I wanted to be an astronaut. One day I was hunched in the back seat of a Cortina with my two brothers, on a long journey to Swansea to see our grandparents. We had been driving for hours. Everything was scratchy and crowded. It suddenly struck me that astronauts would feel like this. There were three of us, just as there would be three crew on an Apollo mission, trapped in a similar amount of space. Why does our experience of travel always have to be so cramped? Orbital is very much about this sort of contradiction. The book has a great feeling of floating freedom, but also takes us into the narrow, metal tunnels full of kit, clothes, laundry, miscellaneous luggage, and jumbled electronics that make up the ISS. We explore space through the medium of claustrophobia, experiencing the endlessness of the universe through one short day, travelling on a vast journey that goes nowhere, orbiting around the same but constantly changing Earth. These ironies seem to be part of all our journeys, through space or otherwise. This writer makes the best of the limits of her approach, like children accept a Cortina, or astronauts accept a capsule, to get to Swansea or the moon. It is a simple truth that limits ironically make exploration possible, no matter what sort of journey you take, earth-bound or space-bound, real or literary.

Anyway, that’s enough work for today. Let’s put the inspection panel back on, and go down to the observation cupola and enjoy the wonderful view.