Best Eight was inspired by an odd fact I came across whilst idly, and accidentally, watching a documentary about rowing. An extremely healthy looking young man was explaining that selecting a competitive, eight person rowing crew was not about choosing the eight best performers on a rowing machine. A good rowing crew is mysteriously more than the sum of its parts. It’s best eight, not eight best. Out of this came all kinds of interesting possibilities. There was potential unfairness in the way a good rower might possibly be passed over in favour of someone less competent. Equally, there was a sense of tolerance in the way we should withhold judgement about who is worthy and who is not. A narrow definition of merit shuts the door on people who have unexpected things to give.

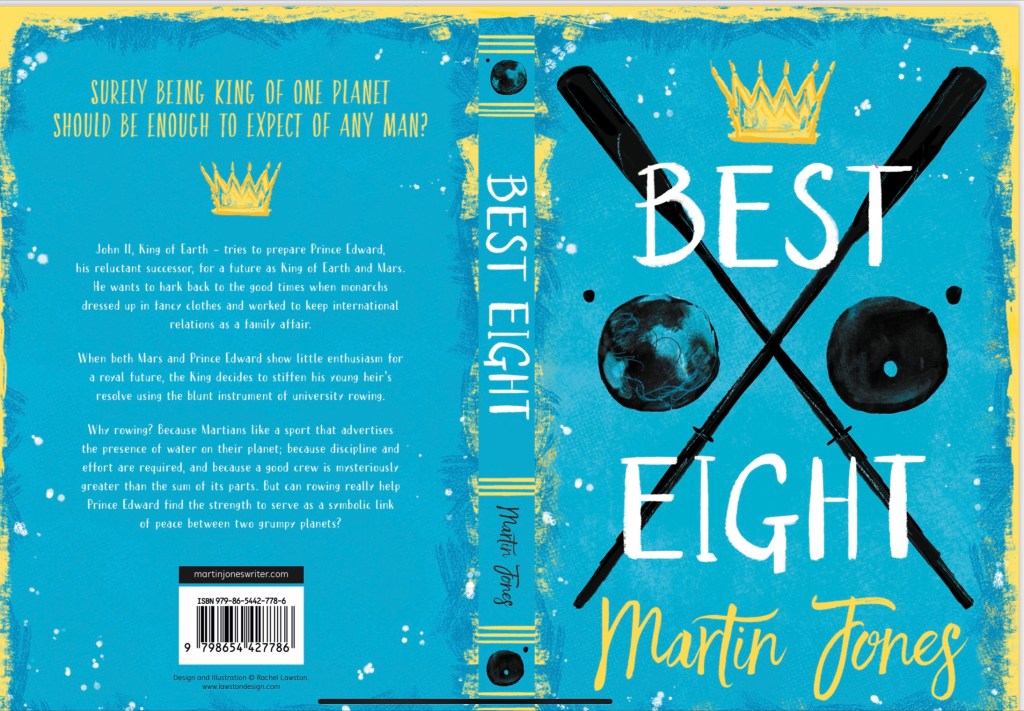

So, I wondered, could we stretch this idea out? Let’s think up a bizarre scenario – maybe at some distant time in the future, a King of Earth wants his grandson and heir to extend the monarchy to Mars. The boy is reluctant to face his responsibilities, so the King decides that rowing might instil the necessary grit. Could there be a place in the Oxford Blue Boat for a future prince, who is quite possibly the worst rower at Oxford University? Could there be some way for this unlikely person to be one of the best eight, even if he is certainly not one of the eight best? And so the game was on. The challenge was to find a way for the prince to win a place in the boat and go on to fulfil his destiny. The other challenge was to take a book set in the future, but playing out in the most traditional of locations, and find a seat for it in the sci-fi boat.

The History Behind Best Eight

This is a brief look at the European royal history that lies behind Best Eight.

Best Eight, is about a royal family of the future trying to use dynastic manoeuvrings to overcome divisions between Earth and settlements on Mars. Unlikely as this scenario sounds, there is plenty of history behind the book’s fanciful future. In our own divided times the UK’s monarchy is a source of national pride. We should remember, however, that until relatively recently, the interests of royalty typically went across borders.

I could go into a lot more complicated detail, but suffice to say the story of European royalty is not about nationalism. In fact a historian with the great name of H.G. Koenigsberger, has come up with the term “composite monarchy” and “composite state” to describe a typical European monarch and their domain.

So for centuries, monarchs had presided over composite states rather than countries. This very much included the UK royal family. Queen Victoria, Queen Elizabeth II’s great great grandmother, was known as “the grandmama of Europe”. Members of her largely German derived family were present in royal courts across the continent. Victoria’s daughter, Princess Victoria, was actually mother of the Kaiser, the monarch of Germany during the First World War. You’d have thought that such fraternal links would have helped prevent something as terrible as the First World War. And, indeed, once they realised the gravity of the situation, Europe’s royals did try to stop what was happening. But despite a blizzard of telegrams between royal cousins in different countries as war approached, they were not able to resist generals, politicians, arms manufacturers, mobilisation timetables and nationalist fervour whipped up by popular newspapers. The war happened, and by its end the three great royal houses of Europe – the Russian, Hapsburg, and German had all disappeared. The British monarchy only survived by hiding an international nature behind a patriotic disguise. George V identified himself with the wartime lives of his subjects, touring hospitals and arms factories. He changed the family name from Saxe Coburg Gotha to the more British sounding Windsor. Other royal titles also had a make-over. It was a question of here’s a map – choose somewhere British, that’s not too industrial. The Duke of Teck became the Marquis of Cambridge; Prince Alexander of Teck became the Earl of Athlone; Prince Louis of Battenberg became the Marquis of Milford Haven; and Prince Alexander of Battenberg became the Marquis of Carisbrooke.

In this way the British monarchy survived, by denying its reality. That reality had been crushed in the nationalism of the First World War. Monarchy had hardly been a perfect system of government – the Russian royal family acted as autocrats, and the Kaiser has been described as a bombastic sabre rattler, who was too late in his desperate efforts to make amends by using his family contacts to try to find peace. But though governments largely ended any role for monarchy after 1918, previous arrangements were perhaps preferable to what followed. The fall of international kings and queens led on to the rise of nationalist dictators, the legacy of which remains with us in independence movements to this day. It is almost symbolic that the trigger for the First World War was the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, heir to the Hapsburg throne, by a Serbian separatist.

So next time you see British monarch held up as a national symbol, it is worth remembering that the history of monarchy does not support this. Best Eight is a whimsical picture of that history translated into the future, imagining the international nature of monarchy making its return.

To see what happened, follow the link below. Enjoy.