The Guest is a 2023 novel by Emma Cline. It tells the story of a young woman called Alex, a hustler trading on her looks. As the story opens, she’s about as close as she’s going to get to settling down, playing the role of dutiful girlfriend to Simon, a wealthy older man. They live at his house in a smart, Long Island beach resort, until a moment of unguarded exuberance at a party has Simon asking Alex to leave.

I soon abandoned my initial assumption that The Guest would be something like Pretty Woman. Do you remember that scene in Pretty Woman, where Edward mistakes Vivienne’s innocent flossing for drug taking? In The Guest there is no innocent flossing. And while Pretty Woman ends with Vivienne winning her rich man, The Guest starts with the rich man dumping the girl. Ejected from his house, she wanders around the local area, surviving on her wits, hoping for a reconciliation at Simon’s traditional Labor Day party five days hence.

I really enjoyed this book but found it hard to review – as in to describe what I liked about it. I was engrossed, as if reading a thriller, every page a cliffhanger. And yet this tension could arise from Alex milling about at boring, pretentious parties, causing very minor damage to valuable paintings, sitting in restaurants telling various men what they want to hear, pretending to be different women depending on the context in which she finds herself.

Maybe I found this book hard to write about, because a review seeks to tie a book down, while Alex, as a character, seeks to escape such a fate.

In her wandering on Long Island she adopts all kinds of roles as part of her little scams. Student girl, rich girl, respectable young lady, child minder, femme fatale. She wants the security of any of these roles but instinctively does not want to become marooned in them, as she was whilst living her seemingly perfect life with Simon. In reality that idyll involved lonely days on the beach while her middle-aged boyfriend pursued an obsessive exercise regime and worked long hours in his home office.

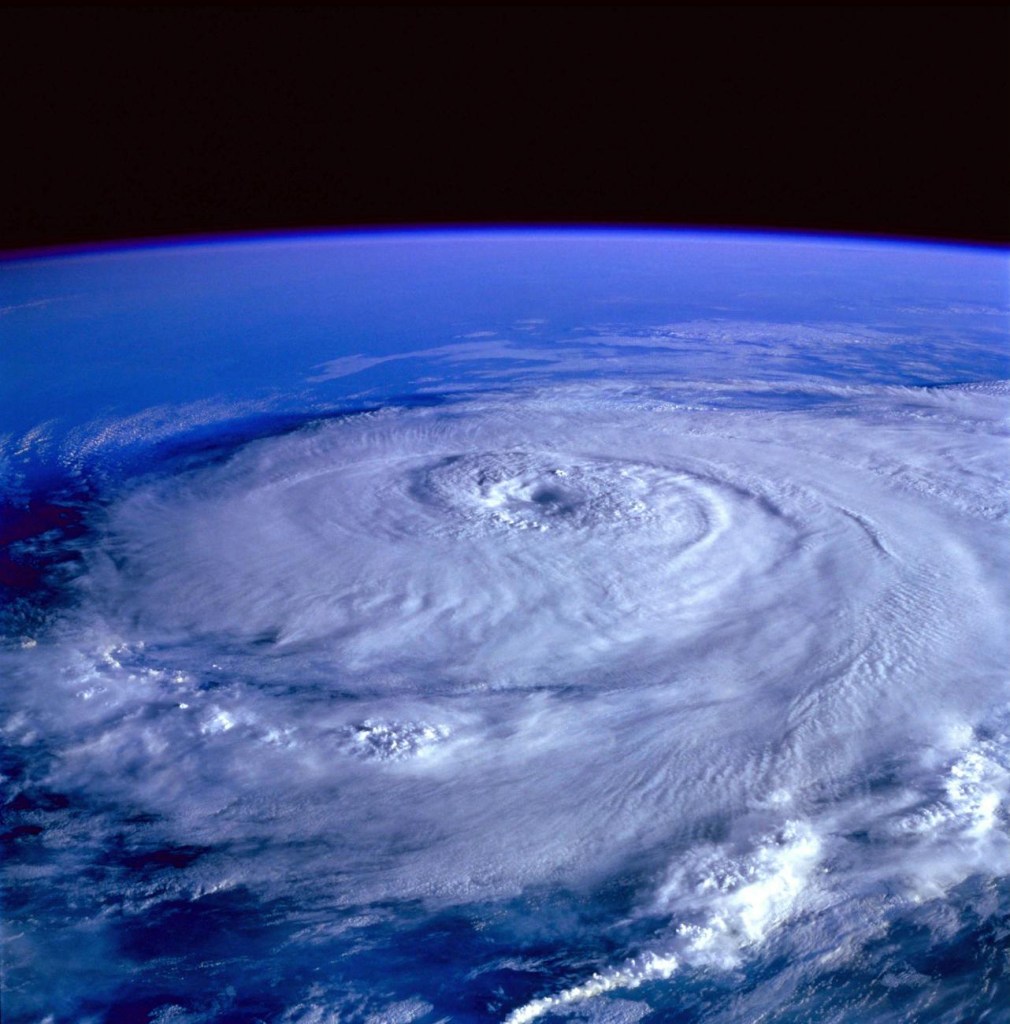

Just before Simon tells her to leave, Alex goes for a swim. Caught in a current, exhausted by futile, splashy efforts, she saves herself by giving up and drifting. This happens to deliver her into safer waters. Alex staggers out of the sea, onto a beach populated by people having a vaguely summery time, unaware that a life and death crisis had just occurred.

This sums up the book really, the combination of peace and danger in one scene. Life at Simon’s house was a lost Eden, and a hazardous quicksand of boredom and loneliness. Any of the other roles into which Alex dips her toe during the book might offer security, or become a trap to be escaped. In the end the security she seeks and the danger she flees are combined. There is a kind of peace in The Guest, like the misleading tranquility of a billionaire’s mansion:

‘So much effort and noise required to create this landscape, a landscape meant to evoke peace and quiet. The appearance of calm demanded an endless campaign of violent intervention.’

The Guest is beautifully written mediation on the nature of security in a dangerous world. Bravo.