Gravity’s Rainbow is Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 novel, set in the final months, and immediate aftermath, of World War Two. It centres on Germany’s V-2 rocket programme, and a quest by a group of central characters to find a secret device, planned for a special version of the rocket.

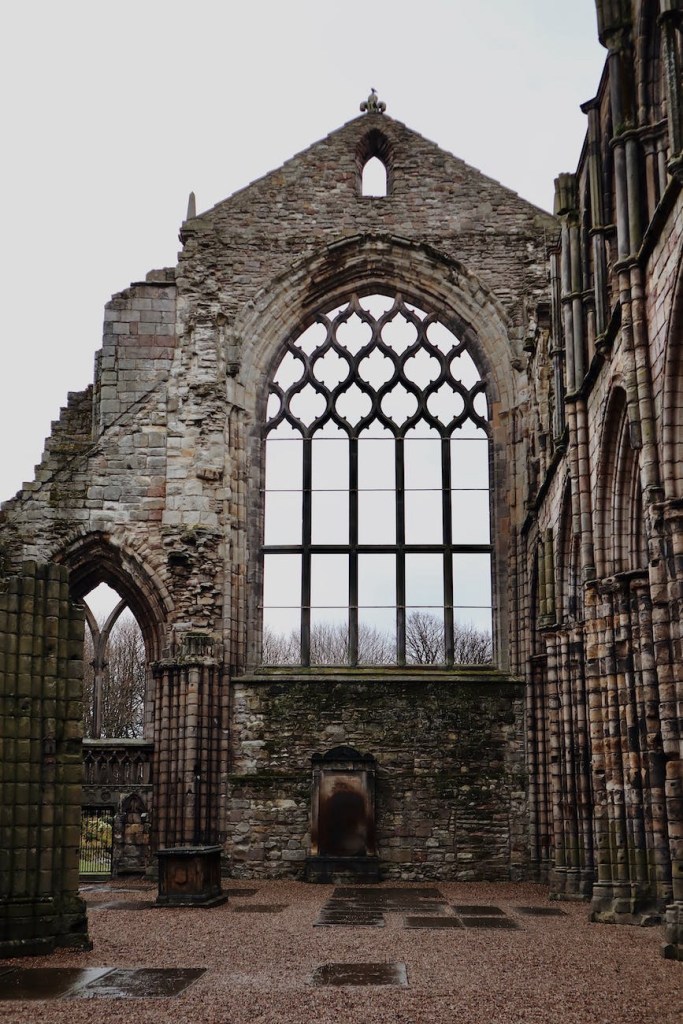

The V-2 was a shockingly powerful innovation, the forerunner of all rockets we see today launching people and hardware into space. As one of the first man-made objects ever to break the sound barrier, the V-2 moved so fast that someone witnessing its impact saw an explosion first, followed by the sound of the rocket falling. Seemingly arriving ahead of itself, the V-2 blurred the difference between past and future, and so began to tear apart the foundations of what we complacently assumed was stable reality. The book’s initial confusion of past and future spreads out to include good and bad, madness and sanity, seriousness and levity, inside and outside. You name some form of organisation, it will fall apart in Gravity’s Rainbow. The psychologist Karl Jung – mentioned in the book – thought there was a shared unconscious which we enter in our dreams, where all the polite categories of waking life fall away. In the world of Gravity’s Rainbow this chaotic dream realm actually mimics real life, where Germany lies in ruins, its borders meaning nothing as troops of many nationalities mill about a wrecked wasteland. Berlin’s population live together in the open, amongst the rubble of former houses. A weird, sometimes beautiful, often profoundly distasteful, nearly always confusing, dream/nightmare is a good description of Gravity’s Rainbow.

In contrast to the fever dream feel, there is also a lot of hard science in the book, chemical bonds and engineering principles related to rockets and the industries that support them. The scientific method involves studying one variable while excluding all others. But in Gravity’s Rainbow it is impossible to separate one variable from another. The subject of astrology comes up quite frequently, a non-scientific subject in the sense that you can never separate one variable from another. You can’t keep Jupiter still while studying the effect of the movement of Mercury, for example. Gravity’s Rainbow is informed by science, but has an artistic sense that life’s variables can’t be isolated from one another.

So does all this make for a good book? I don’t know. Who am I to judge? My personal feeling was that Gravity’s Rainbow might be full of fascinating ideas, but the actual reading experience was patchy, at times entertaining, moving and interesting, but increasingly hard work and exhausting into the later sections. Thomas Pynchon certainly did not follow Hemingway’s writing advice that ‘the main thing is to know what to leave out’. Nothing is left out of this massive novel. Personally, I felt that some of Hemingway’s leaving out would have been beneficial to my reading pleasure. All the oppositions that get demolished in Gravity’s Rainbow include the idea of a good or bad book. This one is both.